- Home

- Rodman Philbrick

Zane and the Hurricane Page 3

Zane and the Hurricane Read online

Page 3

Except that’s not the way it happens.

What happens is this. Bandy waits until I’m almost to him, and then he turns and scampers alongside the guardrail, against all that traffic, like he intends to lead me away from all the scary cars and horns and he hopes I’m smart enough to follow.

Dumb enough is more like it. Because that’s what I do. I follow the dog. In the rain. With a hurricane coming. Dumb and dumber, running back into the storm.

One good thing about the rain. Nobody can see I’m crying.

I follow that dog for miles in the warm rain, through the stink of overheated cars and smelly exhaust fumes. Bandy keeps waiting for me to catch up and whenever I get in range he scoots ahead, wagging his tail and yipping at me like he’s trying to say something. Maybe apologizing, because he must sense how bad I feel, leaving Grammy behind probably worried sick about me, and there’s nothing the pastor can do about it because he has to keep that van going forward in the pressing traffic without even a breakdown lane where he can pull over.

Truth is, I’m doing a really bad thing. I know it, too. Much as I love that stupid dog, jumping out of the van was flat wrong. No question. Chasing Bandy through the rain, alongside all those honking cars, every step I take is the wrong one. But I keep thinking I’ll catch him and then go back and find the van and everything will be okay.

Until Bandy finally scampers down off the highway onto a regular street, into this empty wet neighborhood of saggy clapboard houses, some of them boarded up.

Then I know for sure where he’s going.

“Bandy! We can’t go back! Come here, boy!”

But he won’t stop, no matter how much I plead and beg. He’s trotting along and wagging his tail like this is all a fun game. And me? I’m following in my squishy Nikes, clothes soaked through to the skin.

Not many people are left in Grammy’s neighborhood, but now and then I see a few old gumbies peering at me from behind the wet windows. Shaking their heads because that boy out in the rain, he must be crazy.

They’ve got a point. Anyone with wheels is headed out of the city, away from the hurricane, and I’m letting a little dog lead me in the opposite direction. Crazy and stupid, totally. But I keep trudging along, my voice so hoarse I can barely shout at the dog.

Not that it does any good anyway, shouting for him to come back. Bandy has his own idea that he thinks is right. It started with him running away from the scary dogs, but at some point he decided to take me home, as close to home as he knew. That was his mission and he did it, like he had me on some kind of invisible leash.

When I finally trudge up to the porch he’s quivering with doggy joy, rolling on his back and showing his belly to let me know how happy he is that he led me home, and I followed.

At this point I’m so wet and miserable and scared of what my mother’s going to say that I can’t even be mad at him.

“Don’t suppose you have a key?” I ask.

He barks, wagging his tail.

“Didn’t think so.”

Great. So now I have to break into my great-grandmother’s house, which probably makes me a criminal. I certainly feel like one, eyeing the other houses on the block to see if anybody is watching.

Nobody home, or if they are, they’re not showing themselves.

I try the windows, find one that’s not locked, force it up, and shimmy inside, landing with a thump. Then I open the front door and let Bandy in. He’s like a little sponge, shaking drops in all directions, and I’m not much better. I get a bunch of towels from the bathroom and try to dry us off, but the dog thinks this is a game, and somehow we both end up wetter than when we started.

“Bet you’re hungry, hey boy?”

He barks as if to say yes. No surprise, he’s always hungry.

“Your food’s in the church van,” I tell him. “Maybe we can find something in Grammy’s cupboards.”

There are cans on the shelves, mostly soups. Turns out Bandy likes beef stew. I have some myself, not bothering to heat it up. Tastes kind of weird that way, but I’m so hungry it doesn’t matter.

After slurping up his food Bandy turns around in a little circle and instantly falls asleep with his head on my foot.

A gust of wind rattles the windows. Sends a shiver through me, even though it’s still hot. Funny thing, I never expected to find the house so lonesome. The place was full of Miss Trissy and all her stories and her pictures and her songs, and for some reason me and Bandy don’t seem to fill up the empty.

Thinking about it only makes me feel worse, so I slip my foot out from under the dog and go to that big old black telephone and make that dreaded call to my mom. I’m slotting the numbers in that rotary dial, heart pounding, afraid of what she’ll say. From the moment I slipped out of the van I knew I’d have to make this call, but that doesn’t make it easier.

She picks up on the first ring and goes, “Tell me you’re okay!”

“I’m okay, Mom. We’re at Grammy’s. That’s where Bandy ran to.”

I explain how my cell phone is in my backpack and the backpack is in the church van, so I couldn’t call until I got to Grammy’s house. I tell her how sorry I am for what happened but it wasn’t my fault, I had to do it.

Mom cuts me off and says, “We’ll deal with that later. Your poor great-grandmother is in a state, of course. Pastor Daniels called the police from his vehicle to report a boy lost on the highway but obviously they didn’t find you. With an entire city evacuating, the cops have their hands full, but as soon as we hang up I’m going to call them and wait on the line as long as it takes and give them your location. When they show up, young man, you will let them take you to a storm shelter. There will be no argument on this subject.”

“What about Bandy? I heard on the radio the shelters don’t allow pets.”

“I said no argument.”

She means it, so I shut up.

“I understand you love that little dog,” she says, relenting.

“I thought he’d get run over!” I blurt.

Mom takes a deep breath and then goes, “I’m hanging up to call the police. Maybe there are shelters that allow pets. I’ll call you back as soon as I find out.”

“Okay, Mom.”

“Love you.”

“Love you, too.”

* * *

Hours go by.

The cops never do show up, not that night.

Not ever, actually.

Hours tick by, one long minute at a time. Hours and hours, and the phone doesn’t ring, and it doesn’t ring, and it keeps not ringing.

Outside, in the dark, the wind begins to talk. Well, not talk, exactly. More like little noises shrieking up one side of the roof and down the other, like a pack of crazy invisible monsters coming through the night to get us.

There’s nothing to do but curl up on the couch with Bandy and try to watch TV through the static and wait for the phone to ring. The only thing on Grammy’s one station is the hurricane, the same stuff over and over, and eventually my eyelids get heavy and I must have fallen asleep, because the next thing I know the TV is off and the room is dark.

The whole house is dark.

Black dark, not even a glimmer of light.

The power is out.

Bandy whimpers, trying to curl closer. He’s what woke me, licking my chin.

“Stay here, boy,” I whisper.

Something about the darkness makes me want to whisper.

I feel my way along to the telephone table and lift the heavy receiver, hoping to hear Mom’s voice on the other end, telling me not to worry.

But there’s no one there. The phone line is dead and the wind … well, the wind begins to scream.

A gust slams into the side of the house, rattling the windows. Bandy hunkers down on his tummy, whimpering. Obviously scared of hurricanes. Smart dog.

The storm gets stronger and stronger, until the house whimpers, too.

“We’ll be okay,” I keep telling the dog. Hoping it’s true.<

br />

Then a window explodes, punched in by a falling branch. The broken tree-fingers scratch at the windowsill like a thing alive and Bandy goes nuts, as if he thinks he can scare the storm away by barking at it.

I’m crouched in a doorway in the middle of the house, as far from the windows as possible. Knees to my chin, hands protecting my head because that’s what Mom always said we should do in a tornado. If the roof flies off, don’t look up, that was Mom’s other instruction about a tornado. But this isn’t a tornado dancing through a town, exploding buildings and then going away. Bad as a tornado might be (and it must be terrible), at least it doesn’t last long — it wrecks the world and then moves on. But the hurricane feels like it’s here to stay and getting stronger by the minute.

The wind, the wind, the wind. Please stop the wind.

That’s what keeps running through my mind. Making bets with myself that the storm is about to weaken, that the wind will give up any second now, but I keep losing those bets and the storm keeps blowing.

Please, please stop.

Begging doesn’t work. Praying doesn’t work. Nothing stops the storm. It just keeps on howling and shaking the house.

Darkness melts into dawn and as the sky gets lighter the wind screams higher and higher.

Over the screaming wind a shrill, stuttering kind of noise comes from the street. Sounds almost like crazy laughter, rising and falling, falling and rising. Finally I can’t stand it anymore and crawl over to the broken window to have a look. The crazy noise is coming from a stop sign at the corner of the street. The wind makes the sign quiver violently and bend almost to the ground, but the sign keeps popping back up, as if trying to shake off the great force of the hurricane.

That’s sort of how I feel, like that stop sign, quivering inside but fighting back.

The noises the hurricane makes are like nothing I’ve ever heard before: the shriek of roof shingles exploding into the sky like flocks of frightened birds.

Metal screaming as if in pain.

Ripped-apart trees rising in a whirl, like ingredients in a giant blender.

The eerie snap! and ping! as phone lines and power lines break away from the poles, uncoiling against the wet ground like giant whips.

The hurricane keeps on coming. On and on it roars by like an insane train that never seems to end.

Bandy keeps licking at my hand. He thinks if he’s a good-enough dog I’ll make it stop.

I hug him closer.

Another window explodes. Spatters of rain hit us inside the house. Rain like hard, tiny bullets.

Please stop. Please stop. Please please please.

Here’s the thing about being afraid: after a while it makes you tired. As the hours go by I start to nod off, chin lolling on my chest. It feels like the hurricane has always been here and always will be, so I might as well sleep. The storm invades my dreams and I see my mom with her yellow hair streaming in the wind, yelling words I can’t make out. Miss Trissy is there, too, trying to sing louder than the wind, but she can’t and rain comes from her eyes, soaking me to the skin.

* * *

When I wake up the storm has softened. The wind is still blowing, rattling the world, but the air feels lighter. There’s a patch of blue in the morning sky and for just a moment, no more than a heartbeat, I’m convinced the hurricane was a bad dream. But the branch sticking through the broken window is real, and so is the fact that rain reached deep inside the house, dampening my clothes.

The damp doesn’t matter. We survived, me and Bandy. The worst of the storm is over and the roof is still on the house. Broken windows can be fixed. There’s a funny bubble deep in my chest, like a balloon expanding. Joy. I’m so happy to be alive. So happy we both survived.

“Come on, Bandy, let’s see what it looks like out there.”

Bandy’s still fearful, but he follows me out to the front porch. The wind is coming from the other side of the house and we’re sort of protected from the worst of it. There are leaves and broken branches everywhere, and strange things left by the storm. A pair of new sneakers with the laces still tied together. A plastic bottle filled with milk. A Scooby-Doo pajama top tied in knots. A pink rubber ball. And a little brown bird with a broken neck.

Poor little thing, I’m thinking, poor dead bird.

Bandy barks sharply, as if he senses something off in the distance, and a moment later there’s a deep booming noise, like the sound when you thump the side of an empty fuel oil tank, only deeper. Deep enough to feel it rumble through your bones and in the bottom of your belly.

Not a good noise. Something big and bad just happened. Next I hear a pop-pop-pop, like corks released from a row of bottles, and the fat, wet noise of rushing water.

That’s when I see it with my own eyes. A manhole cover pops into the air, releasing a geyser of brown water. Then another and another, right down the street, one, two, three, four. Torrents of water surge up from the ground, and more of it pours in from all sides, spilling around and under the houses, carrying debris along in the wake.

Enough water to fill the world.

Bandy tugs at my pant leg, frantic to drag me back inside.

Knees shaking, I slam the door and turn the lock, as if that will keep the water out. And it does — for about ten seconds. Then the rising flood gushes through the gap under the door. The pressure of it throbs against the door panels like something alive.

Water squirts through the keyhole and around my fingers. And a whole lot more water gushes over the sill of the broken window, like some huge faucet that can’t be turned off.

Think! Rising water, what am I supposed to do? What did Grammy say?

Rising water drove us up into the attic. She’d pointed at a square panel in the ceiling. Imagine me climbing through that little hole in the ceiling? Well, I did!

There must be a ladder. But where is it? There’s no room for a ladder in the cupboard where Grammy keeps her canned goods. Maybe she got rid of the ladder because she can’t climb it anymore. Or maybe it broke. Or maybe she keeps the ladder outside in the yard, in which case it’s already floating away.

Ladder or no ladder I have to do something. The water is almost up to my knees, which makes it harder to move. Heart slamming, I slog through the flood, fighting my way into the kitchen. Bandy, splashing ahead of me, leaps onto the kitchen table and wags his tail, like he discovered something important — and maybe he has.

“Good idea, boy.”

I grab the rickety table and drag it into the hallway, under the opening to the attic. Shaking like a leaf, I climb onto the table. Standing on my toes with arms stretched high, I’m able to push up the panel that covers the attic opening. I shove it to one side.

It’s black up there, and boiling hot. Steaming air pours from the attic down into the hallway. Even standing on the table, the opening is still too high for me to climb up and inside. Can’t quite get a grip.

“Bandy! Wait here, okay? Good dog!”

I leave him on the table, looking puzzled, while I slog back into the kitchen and grab a wooden chair that’s already starting to float away.

Water is up to my thighs and still rising. Almost but not quite high enough to make the table float.

I have to do this quickly or it will be too late.

Don’t panic, I tell myself, just do it.

Not so easy when water is pouring in the windows and under the doors and streaming through every crack in the old house. Pushing hard, I slog back to the hallway and prop the chair on top of the table.

Bandy instantly leaps into the chair, getting as far from the rising water as possible.

“Smart boy,” I tell him. “You first.”

I climb onto the wobbly table and grab him up in my arms and for once he doesn’t squirm. Balancing on the tippy chair, I boost Bandy the Wonder Dog up into the attic. With the added height of the chair under my feet I’m able to poke my head and shoulders into the attic. It isn’t, as I’d thought, totally dark up there. A little dayl

ight comes through a vent on one end of the building, making me slightly less afraid. Not that I’m really scared of the dark — the night-light in my bedroom went away at least a year ago — but there’s something about total, black darkness that makes my stomach clench.

Bandy, paws skittering on the rafters around the opening, desperately licks my face, urging me to join him.

That’s my plan. But now is when I wish I’d put more effort into gym class. Mr. Carmody the gym teacher made us hang on a bar and see how many chin-ups we could do. I could barely do one. So I made some joke that the whole thing was lame and refused to try it again. Mr. Carmody, he shrugged and said, “It’s up to you, Zane. I can’t make you stronger, but you can, if you put a little effort into it.”

I never did “put a little effort into it.” What was the point? To be ready in case a flood chases you into your great-grandmother’s attic in New Orleans? No way. Stuff like that never happens — except it did! And now I have to do a chin-up because my life depends on it. No choice but to grab hold of a rafter and pull myself into the attic, to escape from the rising water.

Go on, do it. Now or never. Chin-up or drown, your choice.

My whole body is shaking — a kind of heart-slamming weakness that makes it hard to stand up without my knees knocking, let alone hoist myself into the attic. But on the very first try I pull myself through the opening, no problem. I lie there in the attic sweating like a pig, with the rafters poking me in the back and Bandy happily licking my face.

Amazing. Apparently being afraid to die makes you strong — or at least able to do one very important chin-up.

My eyes gradually adjust to the dimness. The attic is hot as an oven and really small. In the center, where the roof peaks, there’s barely enough room for me to turn over and crawl. Except for a few boards near the center of the attic there’s no floor over the rafters. Slip and your knee will go straight through the ceiling, just like in the cartoons.

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery Max the Mighty

Max the Mighty The Last Book in the Universe

The Last Book in the Universe Freak the Mighty

Freak the Mighty Lobster Boy

Lobster Boy Fire Pony

Fire Pony The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg

The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg Rem World

Rem World The Young Man and the Sea

The Young Man and the Sea Wildfire

Wildfire Coffins

Coffins The Big Dark

The Big Dark Strange Invaders

Strange Invaders The Fire Pony

The Fire Pony The Haunting

The Haunting Abduction

Abduction Who Killed Darius Drake?

Who Killed Darius Drake? Brain Stealers

Brain Stealers Things

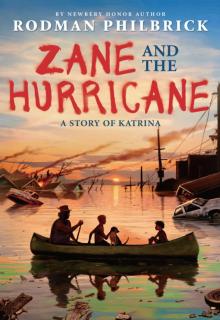

Things Zane and the Hurricane

Zane and the Hurricane The Final Nightmare

The Final Nightmare The Horror

The Horror Night Creature

Night Creature Children of the Wolf

Children of the Wolf The Wereing

The Wereing