- Home

- Rodman Philbrick

Wildfire

Wildfire Read online

Title Page

Dedication

Day One

1. When Trees Explode

2. Run, Boy, Run

3. Your Son Is Missing

4. Don’t Believe in Sorry

5. Beautiful Music

6. Sleep Like the Dead

Day Two

7. Make a Giant “HELP”

8. The Promise He Made Me

9. Between the Fire and Me

10. The Girl with the Raccoon Eyes

11. Dead as a Doornail

12. Not on This Map

13. Okay for a Boy

14. Land of a Thousand Dances

15. The Fart Heard Round the World

Day Three

16. The Sound of Engines

17. Burning the World

18. It’s a Girl Thing

19. Sort of Lost

20. Totally Boogered

21. Secrets Sad but True

Day Four

22. Not Bad for Wonder Woman

23. Hot Snowflakes

24. The Last Branch

25. Home, Sweet Home

26. The Tree House

Day Five

27. Snake Lightning

28. The Only Way to Stay Alive

29. The Bell

30. In Case of Fire

31. Another Greek Thing

32. What Scares You Most

33. Stuff to Worry About

Day Six

34. Burn, Baby, Burn

35. The Rabbit and the Wolf

36. Road to Nowhere

37. The End of the Trail

38. Because, Because, Because

39. No Going Back

40. Ride of the Falconries

41. This Is the End, My Friends

Afterword: About Wildfires

Survival Tips

Sneak Preview: Zane and the Hurricane

About the Author

Also by Rodman Philbrick

Copyright

7 a.m. broadcast from radio station WRPZ, 98.6 FM

“Good morning, campers! This is a wake-up call for my friends at Camp Wabanaski, as requested. Hey, kids, it’s gonna be another day without rain—sixty-five days and counting! The hottest, driest summer ever recorded! Temps in the mid-nineties yet again. Hot enough to burn, baby, burn. That’s according to the Maine Forest Service, so please, no open fires! Only thing we’ll be burning around here is classic vinyl, deep in the groove with your host, Phat Freddy Bell, broadcasting from high atop the lowest official mountain in the great state of Maine.

“Rise and shine, campers! Rise and shine!”

We wake up to the smell of smoke. At first it isn’t too bad, but then the smoke starts to sting and makes our eyes water, and by the time breakfast is over, the counselors say a decision has been made. The fire is still far away enough that we can’t see it yet, but to be on the safe side, Camp Wabanaski will be evacuated as soon as the buses get here.

The smoke is getting worse, a layer of stinky fog that dims the sky. Except along the horizon, which is suddenly flickering orange above the treetops.

Wildfire, moving fast.

“The buses have arrived!” a counselor shouts. “Grab your gear and board! Remain calm but move quickly!”

We’re only allowed one bag, so I jam everything into my hiking pack.

I’m on the second step of the bus, tight in a line of super-excited campers, when I remember my phone is still on the charger. I need it to call Mom and let her know I’m okay. I manage to sneak off without catching the attention of the staff, scoot around the buses, and race back to the cabin.

Sprint down the trail, by the tall white pines clustered around the sign for Camp Wabanaski, “A Summer Experience.” Turn left at the intersection for Lake Path, then right on Cabin Path, and there it is, dead ahead, my cabin.

Inside, the smoke is even thicker. My throat is starting to burn, like I gargled something nasty.

Phone, phone, where’s the phone?! Should be on the rickety table next to the wake-up radio, but it isn’t.

Should I run back to the bus and hope for the best? Answer: yes!

Then I spot a phone under the table. Blue rubber case, labeled with my name, Sam Castine. Grab it up, slip it into my back pocket, and bolt. Screen door slamming like a gunshot behind me.

Whoa! Serious smoke! The buses are no longer visible through the trees, it’s that thick. But I don’t need to see the buses, I know my way back to the entrance area where they’re parked. I have a really good sense of direction. My dad used to say I was born with a compass in my head. Not that I need a compass. All I have to do is follow the trails, Cabin Path to Lake Path, and I’ll be there.

What stops me is a flash of heat. Feels like an oven door has opened over my head. I look up and see something astonishing. The cluster of tall white pines blooming orange flower blossoms from the top. No, that’s wrong. Not flowers. Flames. Flames pouring from branch to branch like a gleaming waterfall of fire. Fat flaming drops dripping on the grass below the pines, igniting it instantly.

The pines explode and disintegrate. A wave of flame erupts from the base of the tree trunks, setting up a wall of fire between me and the buses. A wall of fire that wants to kill me.

There’s only one thing to do.

Run the opposite way.

Run for my life.

Remember me bragging about having a compass in my head? Ha. Must be that fear turns it off, because I’ve got no idea where I am in the world. Somewhere inside the smoke, running away from the heat, like a bug trying to find its way off a hot light bulb. Lungs burning, eyes blinded by the hot, itchy smoke, and the only thought in my head is run, run, run.

Smashing through low pine branches that reach out like scratchy hands. Fighting through sap-drenched undergrowth that grabs my feet. Somewhere along the way, I drop the bulky backpack. Too heavy, too awkward. Keep light, keep moving. Faster. Gotta go faster.

run

gasp

run

gasp

Don’t think, don’t try to figure anything out, because it takes too much energy. If you want to live, you gotta run, boy, run.

Not enough air in the smoke. Can’t breathe, it hurts too much. Iron bands tightening around my lungs, choking me down.

On my knees. Can’t breathe. Can’t run.

Dying?

Maybe. Probably.

What saves me is a gust of wind. I’m on my hands and knees in the weeds, desperately trying to find enough air for one last breath, when something changes.

The wind. It had been behind me, driving the flames, when suddenly it shifts. In an instant the smoke lifts, and through tear-blurred eyes I can see again.

I’m in a patch of low, woodsy undergrowth, surrounded by whip-thin birch trees. Beyond the birch trees, the ground dips into a shallow swamp.

Yes.

Get to the swamp while you have the chance, while you can think.

Crawl, boy, crawl.

No, must go faster! I stagger to my feet, take a deep breath of that fresh, lifesaving wind in my face, and aim for the swamp.

Not sure how long I stay there, lying in the muddy, tea-colored water with my back against a rotting stump. The swamp isn’t very deep. Less than a foot. Barely a swamp at all. Probably the drought has dried it out. But the forest is much thinner, and I can see a chunk of sky, gray and glaring. The stench of smoke is harsh, but it no longer hurts to breathe, and the hot wind stays strong. Maybe the shift in wind turned the fire back, or maybe the fire just decided to go somewhere else.

Whatever, it’s good to be alive. Gives me time to think and plan. How do I find my way back to Camp Wabanaski? Does it still exist? Last time I saw the camp, before the curtain of smoke came down, it was inside the fire. Trees expl

oding. Old wooden cabins, they must have gone off like popcorn.

What about the buses, did they get away in time? And if they did, did anybody notice I’m not there? Will they notify my mom? Sorry, Mrs. Castine, your son is missing and presumed burnt to a crisp.

My phone! Went to all that trouble and almost forgot. Mom won’t have access to family or friends for the first ten days of treatment, but I can leave a message with the staff. Then it hits me like a slap to the head. The phone is in my back pocket. And I’m sitting in swampy water.

I roll over, grab the slippery phone, and desperately try to dry it off. Blowing on the screen and muttering, “Come on, come on. Please work, please!”

Drips of swamp water ooze from a crack in the screen. That can’t be good.

“One last call,” I beg, and hold the button in.

Waiting for the symbol to come up.

Waiting. Waiting.

Nothing.

I lift the phone up to the sky, hoping against hope, but the screen stays dark. That’s bad, but it gets even worse. When I try to put the phone back in my pocket, it slips away, vanishing into the tea-colored water. I paw through the muck, splashing swamp goo, going, “No, no, no, no! Please, no!”

But it’s too late. Way too late. Even if I managed to retrieve it, the phone is for sure ruined by now, if it hadn’t been already.

I want to cry like a baby, I really do, but the heat of the fire has dried the tears right out of me.

Forget the phone. Find your way to a road and get yourself home.

Slogging out of the mucky water, I follow along the edge of the swamp.

My dad had a saying he got from some old TV show. Let’s be careful out there. He always said it with half a laugh, but he meant it, whether we were going camping or hiking or whatever. If he could see me somehow, that’s what he’d say: Be careful out there, boy. And maybe he’d add another of his favorites: Make a plan and stick to it. Something like that.

Easier said than done, but I’ll try.

The swamp I’m following gets narrower and narrower, until finally it becomes nothing more than a dark path, a layer of rotting leaves and pine needles. I keep looking over my shoulder, checking to make sure the fire isn’t catching up. So far so good.

Now, if only I can find a road. A road means passing vehicles, maybe even a police car. They’ll be evacuating the whole area, right? Somebody is bound to see me. Somebody will have a phone so I can let Mom know I’m okay.

So be careful. And the plan? The plan is simple: Keep walking until you find a road, and hope fire doesn’t get in your way.

When the last trace of the swamp disappears, I pick a direction and stick to it as best I can. Trying to follow a straight line through the forest, going from tree to tree. Worst thing you can do, lost in the woods, is start circling.

Hours go by. Or that’s how it feels. Without the phone, I have no way of telling time. Not much of the sky is visible under the canopy of the forest, but I’m pretty sure the sun is lower. Which probably means it’s afternoon. The clock in my stomach is letting me know I’m hungry and thirsty, that I haven’t eaten or had anything to drink since early morning.

The thirsty part is the worst. I keep thinking if only I’d managed to hang on to my backpack, I’d have a couple of water bottles, two energy bars, and dry clothing. My throat is so parched I’m starting to regret not drinking that stinky swamp water when I had the chance. Should I turn around and retrace my steps?

No. Because that would mean heading back in the direction of the fire. Stick to the plan. Be on the lookout for a brook or a stream. Which normally wouldn’t be hard to find, but this is the year of the drought. No rain for months. Heat-wave hot for weeks. All but the biggest rivers have shriveled to nothing.

Hot, hot, hot. My throat and mouth feel like dry, gritty dirt. My eyes are so dry they’re scratchy. Get to a road, boy. Someone will stop, give you water. Drink first, then borrow a phone.

Maybe I should take a nap.

Wow! Where did that come from? Taking a nap in the woods with wildfires raging only a few miles away, that’s like the worst idea in the world. Forget about napping. Forget you’re tired and thirsty. Keep moving. Find a road, get rescued, and drink a gallon of icy cold water.

Maybe just lie down for a minute.

No, no, no. Absolutely not! Keep going!

Thirsty and tired don’t matter. Humans survive for days without water. Banish water from your mind. Concentrate on finding a road.

When I was really little, three or four, I used to sleepwalk. I’d be sound asleep in my bed, and the next thing I knew, my parents would find me in the living room or the kitchen or the hallway, just standing there, still asleep. Weird, huh? Like something in my dreams made me get up and wander.

That’s what it feels like, trudging through the forest. Like I’m somewhere between awake and asleep. My legs keep walking, but part of me is floating along, like a balloon on a string.

Something about being in the woods brings up a memory of Dad taking me trout fishing, the year before he went to Afghanistan. Baxter State Park, which is huge. We hiked five miles from a parking lot to this fishing spot Dad knew about from when he was my age. His father took him, so this was like a family tradition. Told me I would always remember my first trout stream, even if we didn’t catch fish. But we did catch fish. We caught eleven brook trout and kept five to eat over a campfire. So that was the year my father taught me how to cast with a fly rod—I sucked, actually—and build a campfire, and whittle with a jackknife, and how to read a trail map, and a lot of cool, outdoorsy stuff. He promised when I was twelve he’d take me duck hunting, but he never came back from Afghanistan, so that was that.

What would he think of me wandering through the woods with no idea of direction, or where to go, or how to get there? His boy who was supposed to have a compass in his head?

Sorry, Dad.

Sorry, sorry, sorry.

I can almost hear him saying, Don’t give me sorry, boy. I don’t believe in sorry, which was another saying of his, when I notice the ground feels different under my feet. Which kind of snaps me back into paying attention. Looking down, I see a tire track in the dirt. No, wait, two of them, running in parallel. Tracks from a good-sized vehicle, like maybe a big truck.

A road!

Okay, let’s be clear. What I’ve stumbled upon is an old logging road, not much wider than a trail. Cut through the forest long ago, to bring out lumber. How do I know that? Because my dad was a trucker, and when he was young, he drove for paper companies in Skowhegan, hauling pulpwood out of the forest and taking it to the mills for processing. Dangerous work, driving heavily loaded trucks on dirt trails. Make a mistake and the truck can flip over, with all those heavy logs crushing the cab.

This particular road is pretty overgrown. Looks like it hasn’t been used in years. So it’s not like I can stick out my thumb and hitch a ride. On the other hand, I’m pretty sure that logging roads eventually connect with a main road. They’d have to, to bring the wood to the paper mill, right? So it’s really important that I choose the right direction. Go the wrong way, the old road will likely take me deeper into the woods.

Which way? I’ve no idea. How could I?

Make your decision and stick to it.

Thanks, Dad, but that doesn’t really help.

In the end, I flip a coin in my head and turn left.

The old trail winds through the forest, under a canopy of green leaves. Mossy, rotting stumps squat alongside the old trail, more proof that loggers worked this road, back in the day. A lot of the paper mills have closed, which is why my father switched over to bulk tanker trucking before I was born. Hauled everything from milk to gasoline. Made a good living, but nothing like the money they paid him to drive gas tankers in Afghanistan, for as long as it lasted. Combat pay, even though he was a civilian. Money intended for my college fund, and to save for a bigger house, so I’m at least partly to blame for why he took the job in the first pl

ace.

But I’d rather not think about that. Concentrate on covering ground while I’ve got the chance. The light is dim, this far into the woods, and getting dimmer. And the thirst is starting to make me feel light-headed. They say being dehydrated can mess with your mind, and thinking straight will help me stay alive. So I need to find water, and fast.

There has to be water in leaves, right? A drop or two. Tearing a few leaves off a bush, I stuff them into my mouth and chew. Not to swallow, just to squeeze a little moisture into my mouth and throat. But the taste is so awful I try to spit it out, and a piece of leaf sticks to the back of my throat and makes me gag and cough. And cough some more. When it finally comes loose, I’m able to catch my breath.

That coughing fit makes me stop and remember something important we learned in camp. When you’re lost in the woods, you have to think and plan, or risk dying of exposure, which can happen if your body temperature gets out of whack, too hot or cold, or if you don’t get enough water.

Use your brain or die, that’s the rule.

Our camp counselor explained the danger, but most of us already knew. Every year tons of hikers and hunters get lost in the woods of Maine, and we hear about it on TV. Usually they get rescued, but not always. Which makes me remember one of those stories, about a Girl Scout who got separated from her troop on a foggy day, and how she found water by following the mosquitoes. Because mosquitoes are never far from water.

Smart girl.

Never before have I wanted to get bit by mosquitoes. But here I am, trudging along an old logging road in the dying light, so thirsty it hurts. If getting bit by a few mosquitoes is what it takes to find water, so be it.

Come for me, you whiny little monsters. Lead me to water. Lead me to life.

I never do get bit. But as I concentrate on listening for the annoying, telltale whine of a mosquito, I hear something much, much better. A sound more beautiful than music. The gurgle of running water.

It’s coming from deep in the brush, just off the logging trail. I approach slow and careful. Thinking about snakes, if you must know. There are no poisonous snakes in Maine, according to our camp counselor, but I don’t care to meet one, poisonous or not.

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery Max the Mighty

Max the Mighty The Last Book in the Universe

The Last Book in the Universe Freak the Mighty

Freak the Mighty Lobster Boy

Lobster Boy Fire Pony

Fire Pony The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg

The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg Rem World

Rem World The Young Man and the Sea

The Young Man and the Sea Wildfire

Wildfire Coffins

Coffins The Big Dark

The Big Dark Strange Invaders

Strange Invaders The Fire Pony

The Fire Pony The Haunting

The Haunting Abduction

Abduction Who Killed Darius Drake?

Who Killed Darius Drake? Brain Stealers

Brain Stealers Things

Things Zane and the Hurricane

Zane and the Hurricane The Final Nightmare

The Final Nightmare The Horror

The Horror Night Creature

Night Creature Children of the Wolf

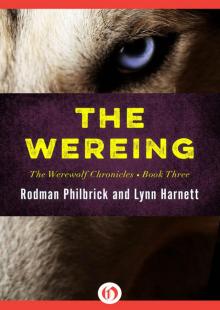

Children of the Wolf The Wereing

The Wereing