- Home

- Rodman Philbrick

The Last Book in the Universe

The Last Book in the Universe Read online

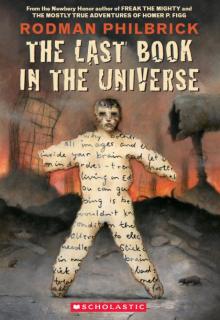

Praise for

RODMAN PHILBRICK’S

The Last Book in the Universe

“Enriched by allusions to nearly lost literature and full of intriguing, invented slang, the skillful writing paints two pictures of what the world could look like in the future — the burned-out Urb and the pristine Eden — then shows the limits and strengths of each. Philbrick, author of Freak the Mighty (1993), has again created a compelling set of characters that engage the reader with their courage and kindness in a painful world that offers hope, if no happy endings.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“There is much to admire in Philbrick’s tale of a postapocalyptic future. There’s stubborn hope and strength of conviction in the book’s moving conclusion, and Philbrick has created some memorable characters in this fast-paced adventure, which will leave readers musing over humanity’s future.”

—Booklist

“Enthralling, thought-provoking, and unsettling, Philbrick’s newest novel hurls readers into the Urb, a bleak future world of gray skies, acid rain, savage behavior, and endless cement. Philbrick’s creation of a futuristic dialect, combined with striking descriptions of a postmodern civilization, will convincingly transport readers to Spaz’s world.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Add this to your library shelves, display it with your quick-pick titles, and share it in your classrooms. Philbrick has outdone himself; this futuristic novel will stimulate thought and discussion among contemporary readers.”

— VOYA

FOR LYNN HARNETT, ALWAYS,

AND FOR EVERYONE

WHO KEEPS ON READING

Contents

Cover

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One They Call Me Spaz

Chapter Two Stealing Is My Job

Chapter Three Those Who Remember

Chapter Four The Girl with Sky-Colored Eyes

Chapter Five Three Rules for Billy Bizmo

Chapter Six The Thing About Bean

Chapter Seven All News Is Bad News

Chapter Eight The Smell of Lightning

Chapter Nine By the Edge We Travel, By the Edge We Live or Die

Chapter Ten Attack of the Monkey Boys

Chapter Eleven Mongo the Magnificent

Chapter Twelve The Problem with Looping

Chapter Thirteen Miles to Go Before We Sleep

Chapter Fourteen Fair Maidens Must Be Rescued

Chapter Fifteen In the Zone

Chapter Sixteen In the Latch of the Vandal Queen

Chapter Seventeen Looking for Probes in All the Wrong Places

Chapter Eighteen Mark of the Assassin

Chapter Nineteen Spaz Boy Melts in the Acid Rain

Chapter Twenty What Bean Believed

Chapter Twenty-one A Sleep Like Death

Chapter Twenty-two Their Terrible Swift Engines

Chapter Twenty-three If the World Were Blue

Chapter Twenty-four What the Cyber Said

Chapter Twenty-five Thinking About the Future

Chapter Twenty-six The Bean Is Back

Chapter Twenty-seven What the Boy Said

Chapter Twenty-eight When They Come for Us in the Apple Trees

Chapter Twenty-nine Say Good-bye to Eden

Chapter Thirty The Sound of Jetbikes

Chapter Thirty-one Fear Itself

Chapter Thirty-two The Last Book in the Universe

Chapter Thirty-three Spaz No More

After Words

About the Author

Q&A with Rodman Philbrick

New Words for a New World

The Next-to-Last Books in the Universe

Original Short Story

Copyright

IF YOU’RE READING this, it must be a thousand years from now. Because nobody around here reads anymore. Why bother, when you can just probe it? Put all the images and excitement right inside your brain and let it rip. There are all kinds of mindprobes — trendies, shooters, sexbos, whatever you want to experience. Shooters are violent, and trendies are about living in Eden, and sexbos, well you can guess what sexbos are about. They say probing is better than anything. I wouldn’t know because I’ve got this serious medical condition that means I’m allergic to electrode needles. Stick one of those in my brain and it’ll kick off a really bad seizure and then — total mind melt, lights out, that’s all, folks.

They call me Spaz, which is kind of a mope name, but I don’t mind, not anymore. I’m talking into an old voicewriter program that prints out my words because I was there when the Bully Bangers went to wheel the Ryter for his sins, and I saw what they saw, and I heard what they heard, and it kind of turned my brain around.

The Bangers have the latch on my part of the Urb, which means they control everybody and everything between Eastie and the Pipe. A million people, maybe more. Nobody really knows how many, because nobody can count that high. Why bother? All you gotta know is, if you live here you’re either down with the Bangers or you might as well be dead. There’s no escape because every part of the Urb is latched by one gang or another. The only escape is Eden, and you can’t get in there unless you’re a proov, and if you’re genetically improved you’d never leave in the first place, so forget about Eden.

I used to belong to a family unit, with a foster mom and dad and my little sister, Bean, but that’s over, and I don’t want to talk about what happened, or how unfair it was. Not yet. The less said about that the better, because if there’s one thing I learned from Ryter it’s that you can’t always be looking backward or something will hit you from the front.

Ryter was this gummy that changed my life, and if you’re reading this, maybe he changed the world, too. Gummies are what we call old people, and the Ryter was so ancient, the hair on his chin beard was as white as bone, and most of his teeth were gone. Even his skin was old and worn out and so thin, it looked like if you held him up to the light you’d see right through him.

The way I got to know Ryter is this: The Bangers sent me to bust him down. As far as I was concerned at the time, he was just another gummy scheduled for cancellation, so why not rip him off?

And that’s exactly what I did.

THE STACKBOX WHERE Ryter lives is out at the Edge, alongside of the Pipe. The Pipe is broken now, but in the backtimes they say it carried billions of gallons of water into the Urb. Fresh, clean water that didn’t have to be boiled and filtered before you drank it. Water so pure, you could swim in it without shriveling. I figure that’s a made-up story, like a lot of the backtimer talk. In case you don’t know, the backtimes were before the Big Shake, when everything supposedly was perfect, and everybody lived rich.

Personally, I doubt the backtimes ever existed. It’s like a story you tell to make yourself feel better, that’s all. The kind of story that starts with my real mom is a rich proov and my real dad is a latchboss and someday they’ll rescue me and we’ll all move to Eden and live happily ever after. Yeah, right. That only happens in the trendies. In real life nobody comes to your rescue.

Believe me, I know.

Anyhow, the stacks. Nobody owns the stacks, and if you squat in one long enough, I guess you can call it home — if home is a little concrete box stacked ten high, in rows of a hundred. They say in the backtimes they used the boxes to store all the things they owned, but the only things stored there now are losers. Assorted mopes and needlebrains, and gummies like the Ryter.

You can smell the stacks before you see ’em, on account of there’s no plumbing and the ’boxers have to use the ground like animals. The strange thing is, at first glance it looks like nobody lives there. Nearby is this old industrial warehouse

that sort of caved in long ago, and the rusty beams and rubble are strewn around, which makes it hard to walk without tripping over stuff. I can hear the scratchy noise of rats scurrying out of my way, and when there’s rats, the humans are sure to be close, but where are they?

Hiding, it turns out. As I get closer, a small, smeary face peeks up from behind a pile of rubble, and then there’s a whistle, a warning signal, and the noise of people scrambling to hide themselves, like they’re afraid of something. Me, probably. They assume I’m one of the Bully Bangers, come to bust them down or worse, which is pretty close to the truth, even if I don’t like to admit it. I’m not officially down with the Bangers, but the gang boss, Billy Bizmo, he sort of likes me for some reason. When he heard I lost my family unit he said make room for the spaz boy, and they did.

So the deal is, I’m here to steal. Stealing is my job. It’s how I stay alive. Either you pay tribute to the Bangers, which means they get half of everything that sticks to your hands, or the Bangers decide you’re no longer among the living. Which makes things very simple, even if sometimes you feel sort of bad about ripping off people who are even poorer than you are.

Steal or die. That’s what it all comes down to. “Be a Banger or Be Gone,” as the saying goes.

Anyhow, this little face pokes up again from the rubble and looks at me with big, scared eyes and I go, “Hey! Don’t move!” and he freezes.

The little face belongs to a little kid, maybe five years old, although he’s got at least a million years’ worth of dirt on his cheeks. I bend down to look at him closer and a tear cuts through the dirt, which makes me feel bad, even though I haven’t hurt the little guy, or ripped him off or anything. Not yet.

“Hey,” I go. “Can you talk?”

Little Face nods. Now there are two tears melting the dirt on his cheeks.

Keeping my voice real low and gentle, I go, “You want a choxbar? All you got to do, show me the way to Ryter’s stackbox. You know where he lives?”

I take the choxbar from my pocket and unwrap it so he can see, but he looks even more scared. I break off half and give it to him and go, “Eat it. Come on, it ain’t going to kill you,” and he kind of flinches and that’s when I realize he’s never had a choxbar and he thinks it might be poison. I break off another little piece and put it in my mouth and go, “Mmmmmm, good,” and finally he eats a piece and waits for it to explode. When the taste starts to hit him, all velvety chocolate, Little Face finally stops crying. “Told you it was good,” I say. “Now what about the geez they call Ryter? Where can I find him, huh?”

Little Face walks me through the rows of stackboxes. He doesn’t say anything; he’s too busy sucking the taste out of the choxbar, or maybe he’s still too scared to talk. Whatever, when he gets to a certain row he stops and just stands there.

I go, “Is this it?”

Instead of saying yes, he runs away.

One of the boxes on the lower row is open. Usually you have to bust down the door, which is why they call it a “bustdown,” of course, but this place is wide open. Like the mope who lives there is saying, Go ahead, rip me off. Which makes me think he could be waiting inside to cut my red and splash me.

That’s how you have to think — real cautious and paranoid — when you’re on a bustdown. Mostly the mopes don’t dare fight back, because of what the gang would do to them, but sometimes you get a suicidal mope, and then all bets are off.

As it turns out, the mope is waiting inside, but he doesn’t try to fight. He’s this gummy with white, white hair and shiny eyes — that’s the first thing I notice, how his eyes kind of light up from deep inside his head. He’s wearing a loose, ragged tunic that’s stitched together, made from even older rags, which means he’s even poorer than most of the curb people.

“Hello, young man,” he goes. “Welcome to my humble abode.”

He’s sitting behind this crummy old crate he uses as a desk, resting his chin on his hands and looking at me with those shiny old eyes. Real casual, like he couldn’t care less about getting ripped off.

“Humble abode” must be backtimer talk for “stackbox” or “crudhole” or whatever, but I’m not there to flapjaw with some gummy old mope. I just want to get in, take whatever junk he’s hoarding, and get out.

That’s when I notice that all his stuff is lined up by the door, ready to go.

“I’ve been expecting you,” he explains. “Word gets around out here in the stacks. You are, I assume, an emissary from the Bully Bangers?”

I nod.

“Come on in,” he says. “Make yourself at home.”

I go, “Huh?” like, What are you, twisted? You want a bustdown? You want to get ripped? Are you brainsick or what? Except all I really say is, “Huh?” because the rest is implied, which is a word I later got from Ryter.

“I heard about the Bully Bangers giving me up,” he says, like it’s no big deal. “Bound to happen, sooner or later. Help yourself, son. Everything of value is over there by the door.”

He points out a tote bag with a few cruddy items inside. An old alarm-clock vidscreen; a streetball mitt so old it’s made of molded plastic; a mini-stove with the power cord all neat and coiled. It doesn’t amount to much, but there’s enough for a few credits at the pawn mart. Better than usual for the stacks.

“Go on,” he says, urging me on. “Take it.”

Normally I would, but there’s something not normal about the whole situation. Like the way he coiled up the cord to the mini-stove. You know you’re going to get ripped and you do that? Is it some kind of trick or what?

It’s like he knows what I’m thinking, because the next thing he says is, “This isn’t my first bustdown. Just thought I’d make it easier for us both. Go on, take it. Take it all.”

“Yeah? What else you got?” I ask, closing in on the old geez. Because he must be hiding something. Everybody tries to hide something.

He smiles at me, which makes his wrinkled old face sort of glow, in a weird way. Like he wants an excuse to smile, no matter what happens. “What makes you think I’ve got anything else?” he asks.

That’s when I see there’s a pile of something under the crate, and he’s been sitting there in front of it, hoping I wouldn’t notice. “What’s this?” I go.

“Nothing of value,” he says, pretending to yawn. “Just a book, is all.”

And that’s when I know he’s lying.

I GO, “LIAR! Books are in libraries. Or they used to be.”

The man called Ryter starts to say something and then he stops, like I’ve given him something important to think about. “Interesting,” he says. “You’re aware that the things called ‘books’ used to be stored in libraries. That was long before you were born, so how did you know?”

I shrug and say, “I heard, is all. When I was a little kid. About how things used to be before the Shake.”

“And you remember everything you hear?”

“Pretty much,” I say. “Doesn’t everybody?”

The old gummy chuckles. “Not hardly. Most of ’em, they’ve had their brains softened by needle probes and they can’t really retain much. Long-term memory is a thing of the past, no pun intended. The only ones left who can remember books are a few old geezers like me. And, apparently, you.”

Now that I think about it, I know what he’s talking about. I’ve always had a lot of old stuff in my head that everybody else seems to have forgotten.

“What else do you remember?” Ryter asks.

“What do you care?”

The gummy gives me a look, like he wants to memorize me or something. “Remembering things is very important to a writer. Before you can put it down on paper, you have to remember what happened.”

“Put what down on paper? What are you spewing, huh?”

He takes a piece of paper from the pile of stuff he’s trying to hide in the crate. The paper is covered with small black marks. I hold it up close to my eyes, to see if there’s anything hidden there, inside the p

aper, but to me the marks look like the footprints of bugs.

“I used to use a voicewriter like everybody else, but it got ripped off,” Ryter explains. “So I went back to basics. I write down each word by hand, like they did in the backtimes. Primitive, but it works.”

I go, “But what’s the point? What are you putting inside your ‘book’?”

Ryter looks at me for a while before he says, “Sorry, son, but that’s between me and myself. I can tell you this much: My book is the work of a lifetime.”

“You’re wasting your time,” I tell him. “Nobody reads books anymore.”

Ryter nods sadly. “I know. But someday that may change. And if and when it does, they’ll want stories — experiences — that don’t come out of a mindprobe needle. People will want to read books again, someday.”

“‘They’?” I go. “Who do you mean?”

“Those who will be alive at some future date,” he says.

Those who will be alive at some future date. I don’t know why, but the way he says it gives me a shiver. Because I’d never thought about the future. You want to be down with the Bangers, you can’t think about the future. There’s only room for the right here, and the want-it-now. The future is like the moon. You never expect to go there, or think about what it might be like. What’s the point if you can’t touch it or steal it or shoot it into your brain?

“What’s your story, son?” Ryter asks, like he really wants to know.

I go, “I don’t have a story.”

Almost before I get the words out, he’s shaking his head, like he knew what I was going to say and can’t wait to disagree. “Everybody has a story,” he insists. “There are things about your life that are specific only to you. Secret things you know.”

When he says “secret things,” a chill goes up from the base of my spine to the top of my head and makes my brain feel numb and frosty. Because there’s certain things I can’t stand to remember and the last thing I want to do is share them with some old gummy.

“You’re zoomed,” I tell him. “Crazy as a cockroach. And I’m out of here.”

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery Max the Mighty

Max the Mighty The Last Book in the Universe

The Last Book in the Universe Freak the Mighty

Freak the Mighty Lobster Boy

Lobster Boy Fire Pony

Fire Pony The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg

The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg Rem World

Rem World The Young Man and the Sea

The Young Man and the Sea Wildfire

Wildfire Coffins

Coffins The Big Dark

The Big Dark Strange Invaders

Strange Invaders The Fire Pony

The Fire Pony The Haunting

The Haunting Abduction

Abduction Who Killed Darius Drake?

Who Killed Darius Drake? Brain Stealers

Brain Stealers Things

Things Zane and the Hurricane

Zane and the Hurricane The Final Nightmare

The Final Nightmare The Horror

The Horror Night Creature

Night Creature Children of the Wolf

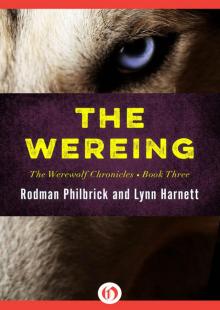

Children of the Wolf The Wereing

The Wereing