- Home

- Rodman Philbrick

Max the Mighty Page 8

Max the Mighty Read online

Page 8

Worm asks me four or five times if I’m okay, which I am once my breath comes back.

The place is pretty dim except where beams of sunlight come through the boarded-up windows and the holes in the roof. The inside is basically one room with a few broken chairs and a tipped-over table with three legs. There’s a big wooden counter along one wall that looks kind of familiar. Then it comes to me.

“I bet this used to be an Old West saloon,” I tell Worm. “Only it was probably miners instead of cowboys.”

The only thing is, it looks a whole lot crummier than the neat old saloons you see in the movies, where Maverick and his buddies are sitting around playing cards and acting cool. You couldn’t act cool in this place no matter what you did.

“How will your dad know you’re here?” I ask.

“He’ll know,” she says. Like that’s final, end of discussion.

I’m feeling my way along in case there’s any more soft spots in the floor. The more I look, the more junk I see. Empty bottles, cracked mugs, a box of candles, a broken mirror in a fancy frame, an old tin of wooden matches.

Worm has her head cocked to one side, listening hard. “Can you hear them?” she whispers.

“Hear who?” I ask.

“All the people who went away. It sounds like they’re whispering.”

“That’s only the wind,” I say.

“I hear something,” she insists.

I go, “It’s just your imagination.”

That makes her frown at me, but she does shut up about the whispering ghosts.

Probably this whole town has been checked out, and everything valuable got swiped. But you never know what might get missed, so I’m poking around behind the old wooden bar when suddenly I feel somebody watching me.

I turn around real careful and slow.

Eyes!

Right in front of me, close enough to touch, these big yellow eyes are looking at me. Real eyes. Eyes that are alive inside. The eyes blink and I can’t breathe or talk or scream out how scared I am.

Below the staring eyes is this strange, sharp-curved nose. Then I realize it isn’t a nose, exactly. It’s a beak.

Owl. I’m staring at an owl, a great big brown-and-white owl, and he’s looking at me like he could care less. It comes to me so sudden that I fall back on my heels and sort of tip over backward, thump!

The noise startles the owl from his perch under the bar and he opens his beak and goes, “Hoooooooo!” He unfolds these huge wings and launches himself up into the air and takes off.

“Hooooooo!” he goes. “Hoooooooo! Hoooooooooo!”

The big owl flaps around the inside of the ratty old saloon and his wings make a whispery sound like “Wissshhhhh! Wisssssshhhhh!”

The Worm never screams, not once. She just stands there and watches, her eyes almost as big around as the owl’s.

After I get over being scared to death, the big old owl starts to look sort of beautiful. It’s amazing how it swoops so calm and cool around the room, wings never quite touching the walls. It doesn’t look like a normal bird, it looks more human because both eyes are in front. It makes you understand why they say owls are wise. Man, this bird looks like it knows everything. How old the earth is, why the sky is blue, where you hid your favorite comic book, everything.

The owl goes, “Hoooooooooooooooooooooo!” and swoops up into the wrecked part of the roof and then he’s gone.

“Wow,” I say, and let out the breath I’ve been holding.

I look over to see Worm staring up at where the owl found a way out to the sky. She’s got this secret look on her face like somehow she knows what the owl knows.

Nothing tastes better than apples and good old American cheese when your mouth is dry and your stomach is growling. After the owl takes off, me and Worm decide it’s time for lunch. I’m expecting she’ll want to go look for her dad first thing, but she doesn’t seem to be in any hurry to find him now that we’re here.

Mostly she just watches me eat. Worm doesn’t seem to have much appetite.

“Apple a day keeps the bad guys away,” I say, trying to joke her into eating.

She just scowls at me and gnaws her apple a little.

“Beans?” I ask. “We could heat ’em up over a candle.”

She shakes her head.

After a while, when my stomach isn’t so empty anymore, I lean back and go, “How come your dad lives in an old ghost town?”

Worm stares at her hands. “Because he does,” she says. “I don’t want to talk about him right now, okay?”

“Okay,” I say.

I’m not exactly surprised when Worm pulls a book out of her backpack. When she doesn’t want to talk about something, she always goes right for her books.

“What are you reading now?” I ask.

She holds the book up. “The Hobbit,” she says. “I’ve read it before.”

“Me, too,” I say.

Worm gets this look like she can’t believe the big goon can actually read a book, and for some reason that really burns me. “What,” I say. “You think you’re the only one who ever read a book?”

She shrugs. “I didn’t say that.”

“No, but that’s what you’re thinking, right? Because I’m this big goofy-looking guy who doesn’t talk that much, I must be dumb.”

She goes, “I never said that.”

“No, but that’s what you’re thinking,” I say. Then I shut up quick, because Worm looks like she’s going to cry. Which proves that I really am a big doughnut brain, even if I do know how to read.

She sits there with her chin on her knees and her eyes closed, not moving at all. I’m starting to wonder if she’s fallen asleep when she goes, “You know what? The first time I read The Hobbit I wanted to be Bilbo Baggins, you know? And live in a hobbit hole underground and have friends like Gandalf the wizard, and go on adventures to the Lonely Mountain, and fight Smaug the evil dragon.”

“Really?” I say. “That’s what I thought, too.”

After that something breaks loose and she can’t stop talking about all these books she’s read, and how much it means to her, and how she’s probably a book addict but she doesn’t care, and how she doesn’t even mind everybody calling her Worm because it’s an honor to be a bookworm even if nobody understands.

“You know what’s really weird?” she says. “All those kids who make fun of me and act like such jerks, they really feel sorry for me, right? But I’m the one who feels sorry for them. They’re the ones who don’t know about how Charlotte saved Wilbur. Or why Old Yeller had to die. Or how the boy saved the dog named Shiloh.”

Worm is so excited she’s punching her fist in the air and her eyes are blazing and her hair is so red and wild it looks like her head is on fire. I’m ready to applaud but I figure she’d probably take it wrong and punch me out. It’s like there’s a whole other person living inside her that only comes out when she talks about books, and that person is so brave that nothing could scare her.

It must have been really miserable being a caveman, before fire got invented. I know because when night comes and it starts to get cold, the first thing we try to do is make a fire and get warm. There’s this little potbellied stove in the saloon and plenty of busted-up chairs and old newspapers and stuff, so I figure it won’t be hard.

Wrong.

The wooden matches are so old they keep falling apart. I’m scratching the side of the box and the heads keep snapping off or going soft or whatever and before you know it we’re down to one match.

One measly crummy match.

That’s when I notice Worm is sitting there grinning in the dark. “We’ll have to use magic,” she says.

“There’s no such thing as magic, except in books.”

Worm shakes her head. “Not true,” she says. “Book magic escapes into the real world.”

She sounds so convinced I decide not to argue. If you think about the raw deal Worm has been getting, you can’t blame her for wanting to believe in

magic and wizards and hobbits. If she can fill her head with stuff like that, she won’t have to think about the bad things that have already happened, and what might happen next if we don’t find her real father.

“I’ll show you,” she says, and holds out her hand.

I shrug and give her the last match.

“Watch and believe,” she says.

Then she takes all of her books out of her backpack and makes a pile on the floor. She opens each book and waves the match over it and goes, “Humnahooah, humnahooah, give us fire, give us light, keep us warm on this cold night!”

After she’s waved the last matchstick over each and every book, she hands it back to me.

“That’s it?” I ask. “That’s the magic?”

She nods. “No problem. Guaranteed to light.”

I look at the measly match and I’m thinking, Go ahead, what have you got to lose? But then my brain says, Don’t be a dodo, you big moron. If the match doesn’t light, that will mean books aren’t magic, and where does that leave the Worm?

Now I wish I’d never tried to light a stupid fire. But it’s getting colder by the minute and all we’ve got is that one old blanket Joe left us, so what choice do I have?

When I scratch the last match on the side of the box, poof! a blue flame pops up and I’m so surprised I almost forget to put it in the stove and light the fire.

“It’s like clapping for Tinkerbell,” Worm explains when we’re warming our hands in front of the stove. “You don’t dare not believe it.”

The real truth is, I still don’t believe in magic. But I’m starting to wonder if maybe magic believes in me.

Just when I’m falling asleep, the owl comes back. He flies in through the hole in the roof as quiet as a whisper. His wings seem to fill up the night. Normally I’d be scared, a big thing like that swooping around in the dark, but there’s a lot of other stuff crowding my brain lately.

So I lay there staring at the glow from the woodstove, trying as hard as I can not to think about the trouble we’re in. Like running away from the scene of a crime and lying about who we are and believing a phony like Frank and escaping from the police. Stupid stuff like that.

My brain is thinking, You better start acting smart, you big jerk, and it won’t let me sleep. It makes me count the stupid things I’ve done instead of counting sheep or whatever. I’m counting every stupid thing I ever said or did in school that made everybody laugh at me, and all the words I didn’t understand back then, and all the books I never read, and all the cool things I wish I’d said but didn’t, and all the time I wasted being mad at the world when I was really mad at me, and that day my pants fell down in gym class, and the time Kevin dared me to eat a tadpole for scientific purposes, and I did and got sick.

All of it starts whirring around inside my brain, the really bad stupid stuff and the just plain stupid stuff and the who cares stupid stuff, until it feels like there’s an eggbeater inside my head turning my brain into scrambled eggs. Which makes me feel even more stupid.

Then my brain has an idea. Leave the girl here and turn yourself in, it tells me. You know that’s the smart thing to do.

You mean leave Worm on her own? I ask my brain.

She’s the one who wanted to run away. She’s the one who wanted to find her real father. So let her. If you stay with her, you’re the one who will get the blame.

Just go? I ask my brain. Sneak away while she’s sound asleep?

Do the smart thing.

Sorry, I tell my brain. I can’t leave Worm, not now. Not here. Not when we’ve come this far. Her dad is going to fix everything.

You’re hopeless, my brain says. But finally it lets me fall asleep, and in my dream we’re back on the Prairie Schooner with good old Dip, and Joe is there, too, and we’re all going home and everything is going to be okay, just like on TV.

In the morning Worm says it’s time to find her real dad.

“He’s waiting for me,” she says. “Out there.”

She’s staring at her hands again, like she doesn’t want me to see what she’s hiding in her eyes.

I go, “You know where he is?”

Worm nods.

“I don’t get it,” I say. “If you know where he is, why didn’t we go there right away?”

Worm shrugs. “I wasn’t ready.”

She’s not going to tell me what’s really going on, or why she’s being so mysterious.

Outside the old saloon, Worm takes a deep breath, squints into the sunlight, and starts marching up the street, like she knows exactly where she wants to go.

I’m tagging along, tripping over my big feet, and saying stuff like, “So what’s the deal? Where are we going?”

Worm doesn’t say anything, she just balls her hands into fists and keeps on marching.

We pass all of these falling-down old buildings, places that once upon a time were a general store or a barbershop or whatever, and we’re heading up the slope toward the mountain that looms over the whole town.

“The railway station,” I say. “He’s at the railway station? Why didn’t you say so?”

The old railway station is the biggest building around, with tons of fancy trim and a steep roof with a big chunk missing. It looks kind of like a gingerbread house except all the icing has melted off. You can tell the people who used to live here must have sunk everything into this one building, to make an impression when visitors came to Chivalry, and maybe to kind of inspire the rest of the town. It didn’t catch on, that’s for sure, and now the train only comes here because it’s a good place to turn around, which is pretty pathetic, if you think about it.

Anyhow, when we get to the railway station I’m expecting some weird old guy to pop out of the woodwork and go, “Hey, kids! I’m Rachel’s dad!” or whatever, and we’ll have to go from there. But when we get there, nothing happens. There’s nobody waiting for us.

Worm stares hard at the building. “Inside,” she says.

“It’s boarded up,” I point out. “We can’t get inside.”

But Worm won’t take no for an answer. It’s pretty clear she’s going to find a way into the railway station or die trying, so we go around back. Only there isn’t any back to the building because it’s built right up against the side of the mountain. And everything is boarded up and nailed shut with these big spikes you couldn’t pull out with a crowbar even if you had one, which I don’t.

Finally Worm finds a hole in the wall. “Here goes nothing,” she says.

“Wait up!” I say. “Hang on!”

But she’s already inside.

It turns out the hole is just barely big enough for a doofus like me to wriggle through if I hold my breath. I end up facedown on the floor with dust in my eyes and that makes it hard to see. But even without seeing you can feel how big it is inside the railway station, much bigger than it looks on the outside.

When my eyes start to clear up I can make out the rows of old benches where people must have waited for the train, and the ticket windows. Everything else seems to blend into the shadows. It can be anything you want it to be, or nothing at all.

But the inside of the station isn’t all dark places. There’s this one beam of sunshine coming down through the hole in the roof and the Worm is standing right inside the light.

“Dad!” she calls out. “It’s me, Rachel! Are you there?”

And then she says it again and again, there-there-there-there. Except her mouth isn’t moving. It’s an echo coming back from someplace deep inside the earth.

Which is impossible but true.

My eyes have gotten used to the dim and dusty light and I can see it now.

A tunnel.

The echo is coming from a mining tunnel that goes straight back into the mountain. A tunnel so big and dark it looks like it wants to swallow up all the light in the world, and us, too.

Something about that old mining tunnel scares me like nothing ever scared me before. Somehow I know there’s evil and misery inside,

just waiting until somebody comes along and lets it out.

“Dad!” Worm shouts, and it comes back Dad-Dad-Dad-Dad.

I may be big and dumb, and a lot of times I won’t listen to my brain, but it doesn’t take me long to figure out that if her real father is down in this old mine, he probably isn’t coming out.

When I get to Worm, she’s shining her miner’s light on a bronze plaque near the entrance to the mine, where the railroad tracks curve into the darkness and disappear.

On the plaque it says:

BURIED IN THIS SHAFT

ARE THE REMAINS

OF SIXTY-SEVEN MEN

WHOSE LIVES WERE LOST

IN THE GREAT CHIVALRY

MINE DISASTER.

MAY GOD HAVE MERCY

ON THEIR SOULS,

AND ON THOSE

THEY LEFT BEHIND.

Worm goes, “Daddy, I miss you so much. Please tell me what to do. Please?”

The echo comes back ease-ease-ease.

My brain tells me I should have known it all along. The reason Worm’s real father has never been there to help her is because he’s dead. We’ve come all this way just so she can visit his grave, and we can’t even do that because he doesn’t have a grave of his own, not like in a real cemetery.

Worm finally notices me and takes a tight grip on my hand. “I was so little when it happened I can barely remember him,” she says. “All I remember is he had this miner’s helmet with a light, and I wanted one, too.”

There’s nothing I can think to say except, “He must have been a pretty cool dad, giving his kid her own miner’s helmet.”

Worm squeezes my hand so hard it hurts, and it makes me think she’s a lot stronger than she looks.

“Do you think he knows about my mom?” she asks. “And You Know Who?”

I never get to answer that one because a new sound comes into the old railway station and starts echoing back out of the tunnel.

It’s a siren. A cop car siren.

I find a crack to look out through the boarded-up windows. The siren has stopped whooping, but there it is, a white cop car kicking up dust as it comes down the main street, heading for the railway station. The cop car has a big star on the side, and SHERIFF spelled out in gold.

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery

Who Killed Darius Drake?: A Mystery Max the Mighty

Max the Mighty The Last Book in the Universe

The Last Book in the Universe Freak the Mighty

Freak the Mighty Lobster Boy

Lobster Boy Fire Pony

Fire Pony The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg

The Mostly True Adventures of Homer P. Figg Rem World

Rem World The Young Man and the Sea

The Young Man and the Sea Wildfire

Wildfire Coffins

Coffins The Big Dark

The Big Dark Strange Invaders

Strange Invaders The Fire Pony

The Fire Pony The Haunting

The Haunting Abduction

Abduction Who Killed Darius Drake?

Who Killed Darius Drake? Brain Stealers

Brain Stealers Things

Things Zane and the Hurricane

Zane and the Hurricane The Final Nightmare

The Final Nightmare The Horror

The Horror Night Creature

Night Creature Children of the Wolf

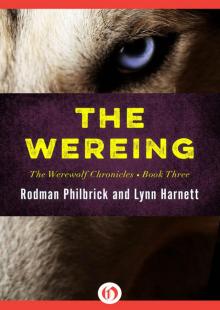

Children of the Wolf The Wereing

The Wereing